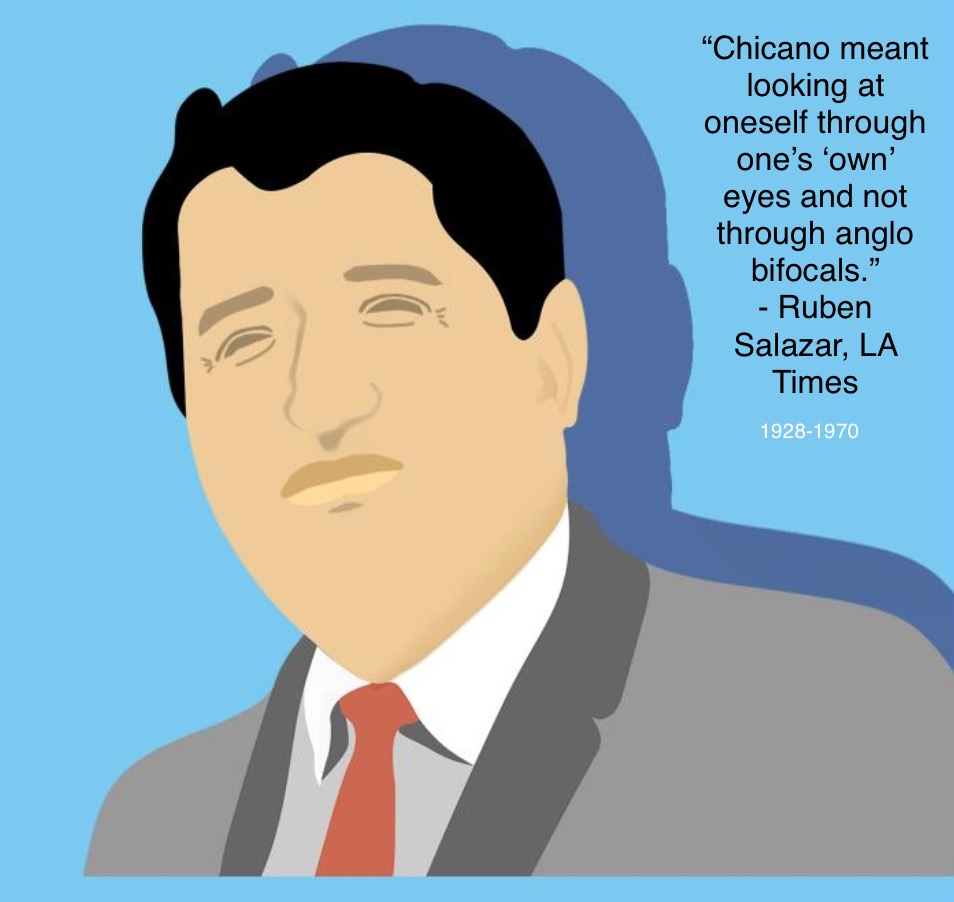

Illustration by Nova Blanco-Rico.

Editor’s note: This is one of the stories that ran in yesterday’s special e-edition of the Bulletin, a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium March.

by Brenda Fernanda Verano, News Editor

When I first told my father I was going to be a journalist, he didn’t take it well. Not just because he had hoped for me to pursue the law degree he had to leave behind when I was born in order to raise a family.

But because he didn’t want his only daughter to be killed.

My father grew up in Mexico, the second most dangerous country in the world for journalists. After we immigrated to the U.S. that perspective was one thing he brought with him to America. And no matter how I tried to tell him that the situation is not as severe here, he was unconvinced.

But I must admit that as I begin constructing my own voice within my writing, I hear a little whisper occasionally asking if my dad’s fears have any legitimacy. Am I digging my own grave as I write about immigration, capitalism, radical education, the working class, nationalist supremacy and other urgent issues affecting people like me, those who I’m determined to report and write about?

These are dangerous times to be a journalist, from being surveilled, attacked by those who are supposed to protect, and criminalized for exposing the truth. I felt shivers up my spine as I scrolled down my Twitter feed during the protests over the murder of George Floyd and saw the pictures of journalists being terrorized and assaulted by police all across the country.

To see the Bulletin’s entire e-edition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium March, click here.

It is impossible to not be concerned when I see my future self in these reporters.

But then I think of Ruben Salazar, a person who would seem to confirm my father’s worst fears. But to me, Salazar is an inspiration.

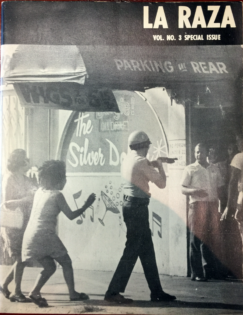

Salazar, a long time LA Times reporter and columnist, as well as news director of KMEX, was killed Aug. 29, 1970 while covering the Chicano Moratorium March. Officially, he was shot in the head with a tear gas canister by an LA County Sheriff’s deputy, who had fired into the bar that Salazar was sitting in.

But to this day, there are some who think that Salazar may have been targeted, a victim of political assassination.

According to a special report from the Los Angeles County Office of Independent Review, “Salazar had told officials of the U.S Commission on Civil Rights in the weeks before his death that he was being tailed because his coverage of police brutality had angered law enforcement officials.”

Salazar was the first person from a major media outlet to extensively cover the emerging Chicano movement. He focused on the full range of problems facing marginalized and racial groups, like police brutality, segregation and educational inequity.

Félix Gutiérrez, an emeritus professor in the Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism at USC and director of the “Ruben Salazar Project” remembers reading Salazar columns every Friday while he was a freshman at California State University, Los Angeles

“At that time [media outlets] didn’t present any efforts to recruit people of color,” Gutiérrez said. “ [journalism] was largely a white men’s business, journalists prided themselves in being subjective and leaving [their identity] outside the newsroom.”

“

Daniel Hernandez, Los Angeles Times

“One of the first signs of a society in decline is a society that does not uphold the standards of a free and independent press.”

Salazar challenged this narrative as his journalism became more personal, and community centered, such as his columns about the unjust treatment of Mexican Americans by the court system and law enforcement.

According to Gutierrez, “Salazar viewed his background, language, culture and his nationality as assets to tell better stories of our people. He showed how one could build an understanding across borders.”

Salazar’s reporting conveyed the struggle and triumph of Chicanos to the outside world. That was until his career-and his life–was cut short while he was doing his job.

Daniel Hernandez, a Los Angeles Times reporter who has previously written about Salazar said seeing how law enforcement in L.A. treated journalists in the last few months feels like “historical deja vu.”

“The repressing actions towards [journalists] during the Chicano Moratorium and the George Floyd protest should serve as a reminder to law enforcement, political leaders and to anyone…that one of the first signs of a society in decline is a society that does not uphold the standards of a free and independent press,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez reminds journalists that undeniable strides have been made in effort to increase the representation of people of color within the media industry, but there’s still a long way to go. He asked me a very important question that made me think about my future and the future of Latinos, “The LA Times has never had a Latino editor in chief or managing editor but we’ve had a Latino mayor, we’ve had Latino sheriffs, so do you see yourself as the first [Latina] editor in chief?”

I understand these are dangerous times for journalists, even in a country with what seems a built-in shield: the First Amendment.. I understand my father’s concern for me. But while concerned, I choose to not see in Salazar’s death as a cautionary tale about being a journalist. I find myself finding inspiration from his career. I believe any potential risks are a challenge worth taking in order to be the kind of journalist he was, one committed to accurately reporting and telling the stories of those whose stories are so often untold or under-represented .

I also find inspiration in people like Gustavo Arellano, a former editor of (now defunct) OC Weekly, who has been a guest speaker for The Bulletin twice in the past three years, and who last week was named the new California columnist for the Los Angeles Times. This is in a time when Latinx Journalists at the paper are demanding more people of color representation in the newsroom, giving people like me and so many others a possible path to becoming professional journalists.

But to me, journalism isn’t about the job, it’s about the work, just as it was to Ruben Salazar. And to be that kind of journalist, I know I must accept any possible costs to do that work. To uphold his values and those of other journalists who hold power accountable, I must withstand the attacks on a free press from the highest office, endure tear gas and police batons, and overcome any obstacles in my path to share my voice and, more important, to share those voices that have been silenced for far too long .

My loyalty as a journalist is first and foremost to the people. They deserve truth and representation, even if it means I put myself in harm’s way.

i would like a hard copy of your special ruben salazar 50th anniversary edition.

Unfortunetely, with so few people on campus, we arevall digital this semester.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of bodies on campus this semester, we are digital only.