By Kelsey Reichmann

Editor-in-Chief

Few people argue that next to a students’ own initiative, nothing is more important to their educational success than the people who teach them. But many students may not realize that just as students are separated into classes (freshman to seniors) their instructors are also divided into different categories. This is the first part of a three-part series in which the CSUDH Bulletin explores the differences between tenured faculty, tenure-track faculty, and adjunct faculty; and how their numbers, or lack thereof, could be greatly affecting your college experience–and future.

Not every professor is a real professor.

Don’t panic: nobody’s faking it, and someone’s title does not necessarily give them any more teaching expertise or knowledge about a subject. But while every person who leads a room full of students is an instructor, some are professors, some are associate professors or assistant professors, and the rest are lecturers. And the difference isn’t just semantics.

Professors are fully tenured, meaning, among other things, they have permanent positions, are hired indefinitely, and can only be terminated under extreme circumstances. Associate and assistant professors are on what is known as the tenure track, a six-year probationary period in which they must teach, publish, engage in research and basically prove themselves worthy of being given tenure. Associates are generally mid-way through that period, and assistants are in the earlier stages.

Lecturers, also known as part-time or adjunct faculty, are instructors with ample professional experience and knowledge in the discipline they teach, but who are either not interested in pursuing tenure, (maybe teaching is a second or part-time job) or are not academically qualified (most tenured faculty have doctorate and master’s degrees).

The general consensus is that the more tenured faculty members at a university, the better it is for students. A 2018 report by a task force examining tenured faculty in the California State University system cited a 2004 study that stated:

“[With] other factors held constant, increases in [percentages in part-time faculty or decreases in full-time faculty are] associated with a reduction in graduation rates.”

In other words, according to that sentence, as tenured faculty numbers drop, student graduation rates should as well.

That is why the CSU is amid a major push to hire more tenured faculty members. Last year, the state granted the CSU $25 million to increase more tenure-track faculty, and one-third of the money in its Graduation Initiative 2025 is for hiring 180 new tenure-track professors across its 23 campuses.

And if a lack of something correlates with the need for something, no CSU campus needs more tenured faculty than California State University, Dominguez Hills, which has the second lowest number in the CSU, and the lowest four-year graduation rate in the system.

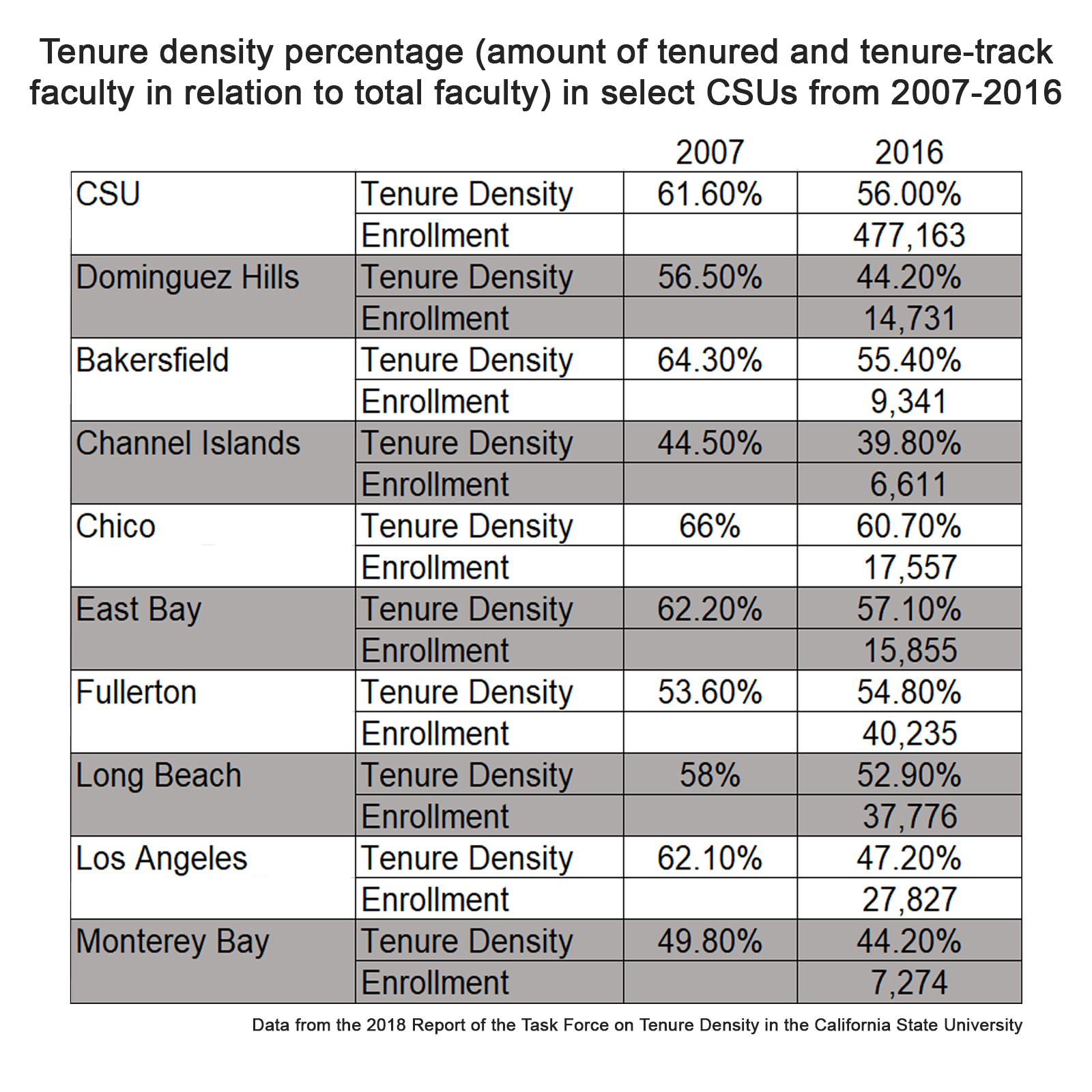

Among the many findings in the aforementioned task force, tenured and tenure-track faculty in the CSU declined from nearly 80 percent in 1994, to around 56 percent in 2016, with the use of part-time, or adjunct faculty, increasing to fill that drop.

At CSUDH, the number of tenured and non-tenured faculty in 2016 was even lower: 44.2 percent, tied with Cal State Monterey Bay and ahead of only the Channel Islands’ campus, which had half as many instructors. Additionally, while the CSU reported that between 2007-2016 tenured faculty in the system dropped 5.6 percent, at Dominguez Hills the drop was more than twice as far: from 59 percent to 42 percent, or 12 percent.

Lack of state funding is a big reason for the drop in tenured faculty across the state. The state legislature passed a resolution in 2001 urging the CSU Board of Trustees to increase tenured faculty at the CSU to 75 percent, but after seven years of requests for money to implement a hiring plan that were never granted, the CSU stopped asking.

Meanwhile, the state sliced its general fund allocation to the CSU by nearly half between 2000-01 and 2013-14. That is often cited as a key reason why tuition has skyrocketed during that time, and why faculty pay raises have not kept up with inflation, leading to periodic threats of strikes. It also kept the CSU from hiring new tenured faculty when older professors retired.

Even though in the long-term a university saves money when hiring new tenure-track faculty to replace tenured faculty (on average, a new hire’s salary is around $77,00 and their benefits translate to $110,000; compared to $92,000 an $132,000, on average, for tenured faculty, according to the 2018 task force report), there are short-term costs, including an estimated $15,000 to recruit potential faculty members, as well as an estimated $50,000 for start-up costs, such as travel and moving expenses.

In other words, if the CSU were to hire 600 tenure-track faculty annually, the $13 million it would save iin compensation costs, would be more than offset by $39 million in one-time costs, or a net deficit of $25.8 million.

Like every CSU, CSUDH has had less money to work with to hire more tenured faculty. But why its numbers are near the bottom of every CSU, and why its percentage dropped more than twice that of the state average over 10 years, is anybody’s guess.

“I can say that one culprit may be enrollment growth,” CSUDH Vice Provost Ken O’Donnell said. “Unlike most of the CSUs, we haven’t declared impaction, and so our additional faculty hires are quickly offset by additional students.”

However, Dr. Kirti Celly, a management and marketing professor who sits on the executive board of the academic senate as well as being chapter chair of the CFA, said she believes CSUDH’s low tenure numbers relate to CSU funding and our “non-traditional” student body (this will be further addressed in the second part of this series on April 25).

What isn’t a guess is that CSUDH, more than any other CSU, has depended on adjunct faculty to fill the gap. However, that is changing. The university, like the entire CSU, is actively recruiting more tenure track faculty.

But while the push to hire more tenure track faculty seems simple–just hire more of them, right?–the process is quite complex.

To reach full tenure, instructors must survive a six-year process known as tenure track, a probationary period which involves scrutiny of decisions they make and requires publication of research.

But what is the point of hiring professors who cost more money, are harder to terminate, and putting them through such a rigorous six-year process, when there are people who will gladly work as adjunct faculty?

Because, theoretically, tenure track and tenured professors are supposed to give more to the campus and, in turn, students.

Being on the tenure track, in most colleges, requires a doctorate, and as a tenure-track professor, you are required to publish research. There is also an expectation that tenure-track and tenured professors will be more involved in the university, participating in councils, the academic senate, or other activities.

Tenure track and tenured professors are also expected to be more available to mentor and help students because they are committed to one university instead of working at multiple ones like some adjunct faculty do.

CSUDH Provost Michael Spagna said there is a balance that tenure-track professors must walk; on one side they must be involved in demanding, cutting-edge research, and on the other, they must effectively teach in the classrom.

One area of concern about hiring more tenure-track faculty is that adjunct faculty, which CSUDH has relied on so extensively for so long, may be phased out. While some adjunct faculty may aim to transition to tenure track, according to the CSU report on Tenure Density, this only happens to 10.5% of them. (The Bulletin will address this in the third part of this series, May 9.

Currently, all the tenure-track hiring being considered on campus is in terms of expansion, Mitch Avila, dean of the college of arts and humanities, said. This is in response to the boom of students that the university is receiving now.

“We are seeing 70% enrollment growth,” Spagna said.

The College of Health, Human Services, and Nursing went from 200 to 800 students in 10 years, Dr. Gary Sayed, dean of the College of Health, Human Services, and Nursing, said.

While every CSU is looking to hire more tenured faculty, the need at CSUDH isn’t just about raw numbers. It and Cal State Los Angeles are the most ethnically diverse campuses in the CSU. In fall, 2017, the campus reported 46.2% of students were Mexican-American, 13 percent “other Latino,: 12.3% African-American, 7.9% white, 5.2 %Asian, 4.2% Filipino. The desire to have an ethnically diverse faculty is self-evident. Yet, in fall, 2016,, the only number that came close to matching up was African-American professors, at 7%. More than half of full-time faculty reported as white, 52.4% and 13.7% as Hispanic/Latino.

The full-time faculty and gender numbers are a bit more equal, with woman comprising about 64% of our student population in fall, 2018, and womenvmaking up nearly 55% of faculty in fall, 2016.

CSUDH Vice Provost O’Donnell said CSUDH is focusing on increasing its diversity. He said a grant from the CSU Chancellor’s office has been “helpful,” in contacting prospective tenure-track faculty across the country, flying in candidates to visit the campus, and offering them financial incentives to come to CSUDH.

While the need to hire more tenured faculty is vitally important in the present, particularly at a university that has had so relatively few compared to other CSUs historically, it’s also about tomorrow, O’ Donnell said, and he hopes that many of our future tenured faculty are currently our students.

“We are the pipeline for that future faculty,” O’Donnell said. “It’s something Dominguez Hills is uniquely qualified to do because we have such a diverse student body.”