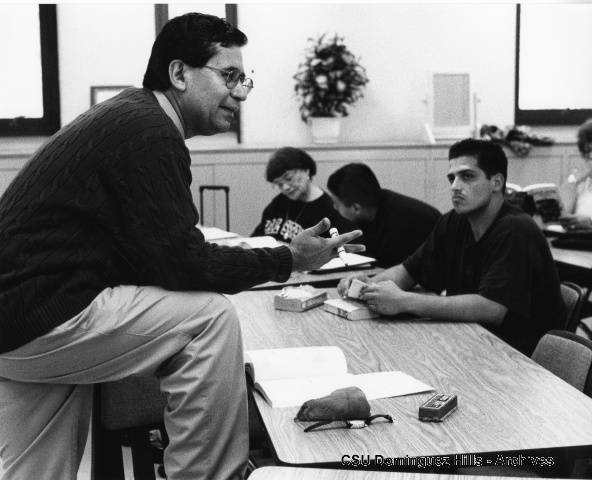

Professor Emeritus, Miguel Dominguez, played a vital role in shaping the Latinx experience at CSUDH. Photo Courtesy of California State University Dominguez Hills Photograph Collection

By Maya Garibay-Sahm, News Editor

In 2020, California State University, Dominguez Hills, ranked in the top 50 universities, in educating and graduating Latinx. CSUDH ranked 25th for bachelor’s degrees conferred to Hispanic students and 35th for the highest enrollment of Hispanic students.

Soon after, the school was named Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) Leader by the Fulbright Program in 2021. The university prides itself on being a diverse campus, with 64% of the students enrolled being Hispanic/Latinx, but that hasn’t always been the case.

Miguel Dominguez, founding chairperson of the Chicano/a studies department, former chairperson of modern languages, and past acting associate dean of the college of arts and humanities, first arrived at CSUDH as a part-time faculty member in 1987. There were no Chicano/a studies department or Latinx staff and faculty at the time. Dominguez estimates that at the time he arrived, only around 10% of students were Latinx.

Prior to Dominguez’s arrival at CSUDH, the Mexican-American studies program was managed by a chemistry professor since there was not a lot of stability in terms of faculty and student engagement at the time. However, because of their wish to keep the program going, Dominguez, who became the professor in the interdisciplinary Mexican-American studies program created in 1970, was given the help of various professors from different departments.

By 1990, nearly 8 million foreign-born Latinxs lived in the U.S., with the population surging four times during this rush in migration in the 70s and 80s. Dominguez recalled how the Latinx community was tiny but mighty when he arrived and helped spearhead the movement that created aspects of a more inclusive university as the Latinx population grew.

With this growth , there was a need to turn the program into a department. Programs have no tenured professors and are more susceptible to being less supported or canceled, whereas departments are able to recruit professors.

“When I arrived, I saw what was happening, and I put more and more time into the department growing the majors and the minors and creating new courses,” said Dominguez. “I delivered to the university a proposal packet with reasoning for turning that program into a department.”

“There was no pushback in the sense that those in the upper echelon of administration, particularly president Detweiler, saw a need to make a statement that the university was committed to the surrounding community or surrounding Latinx communities. But we had to do our homework. In the sense that it wasn’t just done like a fiat- here’s the department, that’s it. We had to put together studies and rationale. And I didn’t do that by myself,” he said.

Dominguez established the department in 1994. His team and himself doubled the number of courses to create a necessary nucleus and more choices for students, including pre-Columbian literature, folklore and customs, Mexican revolution through literature , and art and music, all of which he taught himself.

They then decided that the name of the department would be crucial.

“I changed the name of Mexican-American studies because I don’t identify myself as Mexican-American,” said Dominguez. “First of all, it’s English, the Spanish community doesn’t use it, and it’s redundant. So we chose a label that was more reflective of the history.”

Dominguez felt a need to establish a Latinx Staff and Faculty Association in the early 90s, along with a group of around 10-12 Latinx faculty and staff members. They aimed to form an organization that would host events to foster a greater understanding of Latinx culture and push for programs that would lead to higher success and graduation.

The program hasn’t been as active since, but he feels it may be because many of those needs have been met. Dominguez has been a part of some of the campus cultural changes that make CSUDH representative and rich in Latinx culture.

“We fought 30 years ago to have more access and students have more success in a bachelor’s program, but the glass ceiling still works,” he said. “There’s still a lot to be done. Challenges have come up and new situations.”

Dominguez feels there may be room for improvement in transitioning Spanish-speaking students into an English educational learning setting and that people must always continue to recognize where Latinx students stand and what they may need from the university.